Where does our love of garlic come from?

by Cindi Sutter, Founder & Editor Spirited Table® - All content provided by Bare Bones. Featuring weekly-ish essays on food, family and what nourishes us from Beth Dooley and Kip Dooley.

Aug 23

Garlic, like herbed sea salt with peppercorns, is a sharp little thing us Dooley cooks simply can’t do without. Our ancestors hail mostly from the British Isles, where garlic was either unknown or reviled until after World War II. That our senses now perk rather than pucker at its pungent aroma is a testament to the forces of history and migration. Disdain for the flavors and flourishes of Southern Europe — whether racist, nativist, or just in good jest — is as strong in our lineage as boiled beef.

The mere thought of so many golden-brown potatoes in the bowls of my Irish ancestors, slathered in butter and crusted in salt but missing that dark, sweet underbite of garlic – oh garlic, chopped fine and nesting in the flaky, dense layers of spud – feels to me like a minor tragedy.

Whatever might be said about the effects of globalization, we must also acknowledge it as the reason our bland-palleted ancestors finally came, thank God, into contact with garlic.

Though mere contact, it should be said, doesn’t necessarily lead to love. My Irish-descended paternal grandfather, after four years of fighting the Axis powers in North Africa and Italy, maintained a bland palette, except when it came to anchovies, which he ate prodigiously on saltine crackers. A full thirty years after the war, he turned down a trip to Italy – my grandmother’s idea of a retirement adventure – because the country had, and I quote, “too many Italians.”

So perhaps it was my maternal Grandmother, Elizabeth Flower. Perhaps she nurtured in my mom, Beth, not only a love for cooking, but a specific love, a love for garlic, through a precise, formal lesson some summer night in her seaside kitchen on sauteeing oysters or simmering a French onion soup; or maybe it was simply in the air always, an aroma no longer foreign but familiar.

Gram Flower was quite attached — perhaps militantly so — to her husband’s Scotch and English ancestry. (“She thought everyone should just act like the British,” her daughter Liz, my 91-year old Nanna told me recently over a luncheon of egg salad and poundcake.) But garlic-heavy French cuisine was in favor among WASPs by then, a class Gram Flower married into at the height of our country’s first war with Germany. Determined to make permanent her transition, and therefore her descendants’ too, from German-American to “real” American, she left us a whole suitcase of genealogical records to prove blood connection to early English settlers. On the backs of thin black and white photographs, and in the letters she wrote to archivists around the country — typed out, in fact, on white and blue letterhead from Mrs. Walter C. Flower — her own family name, Schmidt, hardly ever appears.

A rare photo of Gram Flower (right) and her two siblings in traditional German dress. 1904, photographer unknown.

Or, if it wasn’t from Gram Flower, then perhaps we got our love of garlic from my mom’s Dad, Mark Anton, the son of a rowdy industrialist and state Senator with Mafia ties (which at the time, in Jersey politics, was basically, like, a business license). Poppop Anton was propane exec and sailor who really knew how to have a good time. Gram Flower was slow to warm up this Mark J. Anton when he wooed my Nanna down at the shore. Sure, he was rich and connected, but he was a Catholic, after all.

It’s these Anton men from Alsace who gave us our hedonist streak, along with our charisma, our way with people – especially when good food is around. Any moment with Poppop could turn into a feast.

I remember watching him one evening at the shore, dumping balsamic vinegar on sliced avocados. That tang on creamy texture reminds me exactly of roast garlic, a late-summer garnish that gives an earthy savor to roasted corn bruschetta, or fresh basil and tomato, without weighing down their sweetness.

So I advise you now, friends, to snag an extra bundle this weekend at the market, and toss it in the oven. Roast garlic may be the thing you didn’t know you needed.

A Brief Guide to Garlic

Unlike salt and pepper, good garlic has a season, now, late summer. Fresh garlic’s flavors announce themselves as soon as you break the clove open – a far cry from the heads you’ve kept since the winter, aroma-less and sprouting in a bowl by the sink. Toss those in the compost and get thee to a farmers market.Look for a grower who sells multiple varieties. As I learned from a garlic grower at the Bayfield Farmer’s Market, some are best roasted, others whisked into vinaigrettes or simmered into sauces.

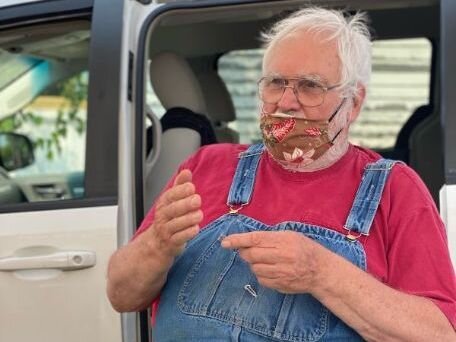

A garlic grower near Bayfield, Wisc. / Alli O'Connell

He also explained to me also how Garlic, like wine, reflects the soil in which it’s grown. Terroir, a word that makes you sound smart when talking about wine, is French for “soil,” or “land.” While garlic might not have sommeliers, there are many, many varieties within its two main categories:

Softneck garlic is, with all due respect, a bit soft in the neck. It’s often braided and hung from walls, and has a long shelf life. Each bulb produces up to forty cloves, hence the nickname “artichoke garlic.” In general, softneck varieties tend to be mild, and work well both cooked or fresh in vinaigrettes and pestos. It’s the all-around garlic, and in the U.S. is mostly grown in California.

Hardneck garlic thrives in colder climes and should be used right away. It’s perfect for zesty salsas or fresh tomato sauces, and its verdant, curly scapes grow into bulbil, miniature cloves that grow from the mother plant and whose name one can't pronounce without sounding Eastern European.

Store your garlic at room temperature in a cool dark place, out of direct sunlight to prevent over-drying or sprouting. Mesh or paper bags allow ventilation, unlike plastic. Only peel it just before you use it.

And please, please, if you take just one thing from this overwrought post about how to use garlic, please do not use a garlic press. They tend to trap little pieces of the crushed clove that linger and become terribly bitter and gross. Plus, garlic is easy to peel and mince, and it makes your hands smell amazing. Turn the clove on its flat side on a cutting board and smash it with the broad side of a chopping knife. The papery skin becomes easy to peel. Mince it, smell it, and toss it into a pan of onions once they’ve browned, or a stir-fry just a few minutes before the food is done (beware, garlic burns).

My favorite way to enjoy a crop of garlic is to roast up several heads to slather on bruschetta, toss with pasta, or whisk into vinaigrette. When roasted, the garlic mellows, goes soft, becomes nutty, and dare I say, divine.

Click Roasted Garlic Bulbs for recipe.